Continuing with our occasional series on Universal Truths, this week it’s “Don’t assume, check!” You know that feeling you get in your gut when you’ve just set off on vacation, and 5 miles down the road you think “Did I turn off the gas?” When the pan is on the stove and baby’s on the move, did you shut the kitchen door? Yes, we’ve all done it, and like that last example, it can get really serious. But to me, it’s always been particularly associated with the military, as we will see.

Let’s go back to the mid-seventies, the height of the Cold War. It’s 4 a.m. over a wild and stormy north Atlantic. Between the 30-foot waves and the oily black clouds just 1000 feet higher, a British reconnaissance aircraft is on patrol, buffeted by the storm around it.

|

| Cat . . . |

Inside the plane, the 12-man crew are busy in a tense game of cat and mouse. They are stalking a Russian nuclear missile submarine. Below the waves, its black hull slices through the calm deeper water, unaware of its pursuer, en route to a patrol area off the eastern seaboard of the USA.

|

| . . . and mouse. |

On board the plane the radio crackles into life. A message is received telling the crew to remain on patrol for an extra hour, the American aircraft taking over from them has been delayed, and they must maintain contact with the submarine until relieved. The message ends: ‘The weather back at base is good; you can use your diversion fuel’. (A reserve of fuel held in case bad weather forces the plane to land elsewhere.) An hour later, and still no sign of the relief aircraft. They wait until the last minute, but finally the crew have to leave, the fuel level is getting low.

When the plane arrives back at base, a strong weather front is passing through, visibility is down to zero. For 20 minutes the crew try in vain to find a gap in the clouds so they can land. Meanwhile the fuel level reaches critical. At last a break in the weather appears and the plane lands just on fumes and the silent prayers of 12 airmen, including yours truly.

At the de-briefing, there were red faces all round. The operations staff controlling the plane had assumed the weather would be good back at the base, and hadn’t checked the latest forecasts. The crew assumed the controllers had checked this, and so didn’t check themselves. If we hadn’t been able to land we would have had to ditch in the sea, losing a valuable aircraft and putting the crew at risk. That’s when I learnt not to assume, but to check – always.

Travelling further back in time, and in rather more illustrious company: June 25th, 1876; the Battle of the Little Bighorn and General George Armstrong Custer.

|

| General Custer and dog. |

Whilst the rights and wrongs of Custer’s actions continue to be debated by historians and generals alike, at least two military assumptions contributed to his defeat:

Firstly, the US Army’s estimate of the number of Indians it would encounter in the campaign was based on assumptions made from the inaccurate information supplied by Indian scouts and agents. What had been assumed as a force of some 800 was in reality a force in the region of 2,000.

Secondly, as he surveyed the Indians’ village on the morning of the battle, Custer could see no men about the place, only women and children. He assumed the braves were still asleep in their tepees. In fact, they had already left, prepared for battle.

Finally, he most likely assumed that, should he encounter difficulties, his pack train, under the command of Captain Benteen, would quickly come to his assistance. In the event, Benteen’s men had problems of their own, and although they heard rifle fire from Custer’s troops signalling a need for assistance, were already involved in a fierce fight.

These assumptions cost the lives of Custer himself and all his troops at Little Bighorn. Assumptions had been made, checks had not, and so 268 lives were lost.

Interestingly, it’s often assumed that the sole Army survivor of the battle was the ironically named ‘Comanche’, a cavalry horse. But I checked, and found that other horses survived, taken by the Indians, and 1 dog, perhaps one of Custer’s very own, for they always travelled with him.

|

| Comanche, who survived the battle. |

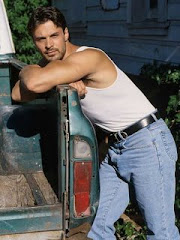

Back to the present. Take a long look at this young soldier.

He’s what, 23, 25? Hard to tell, those eyes are an old man’s eyes. They’ve already seen too much of life and death. That face, it’s been around the block a few times, 3 or 4 tours in Afghanistan? Do you think he’s survived by assuming and not checking? No, I don’t either. But when he comes home, then what happens? Suicide rates among troops returning from active duty have begun to show an increase this year. Figures from the UK tell a similar tale.

Here’s a post from Stan at Metro Dystopia on suicide rates among veterans (thanks Stan).

So don’t assume when our soldier comes home all will be well. Check with your local veterans groups and associations, your elected representatives; ask them what is being done to help our servicemen and women. You might be able to help yourself.

4 comments:

It is easy for us the hide our heads in the sand while other suffer the horrible consequences of wars fought "in our name".

Davis, One example I was going to use for this post was Tony Blair getting the UK involved in Iraq on the 'assumption' they had WMD. I don't think they've found any yet, so, as you rightly say, another war fought 'in our name'

Well put Davis, sometimes our 'Leaders' assume too much.

All too true, too often. Which is why I see a distinction between "supporting our troops," which is good - and "supporting the war" that some asshole decides to start, which is bad.

Post a Comment