A guest post by my truckbuddy Tim from England, now resident in Spain:

A while ago I said Russ and I had been planning a piece to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of World War Two in Europe, and in particular our fathers’ adventures in it. Well here is Part 1, which takes us to the end of 1943. Next week Part 2 will follow Bill and Ted to VE-Day and beyond.

It is sadly typical of most father-son relationships that the son never thinks to ask the most important questions of his father’s life until it is too late. And especially something like their wartime experiences. Most men of our fathers’ generation, those who served in WWII, couldn’t wait to return to normality after the years of conflict. They placed their memories and experiences of those years in a box marked ‘Do Not Open’, what is now termed ‘compartmentalising’. And we, of course, being young, thought war a glamorous adventure and didn’t comprehend our fathers’ reticence when asked about the subject. And when we grew and matured, and could better understand their experiences, all we had to go on were fragmented verbal histories and any mementos our fathers left us.

So this has been a voyage of discovery for Russ and me. My father, Ted, left a treasure trove of documents and bric-a-brac from the war, which, somehow, has survived and ultimately come into my possession. Sadly, Bill died just as Russ was approaching manhood, and he left few mementos of his wartime exploits. A few coins from France and Belgium, even a NYC subway token. And a few buttons and insignia from his uniforms. “All fun to look through when I was a kid,” recalls Russ. However, Russ and I have been able to add some detail to what is available and we enjoyed the detective work. It was gratifying to be able to find some more pieces of the jigsaw!

By the way, I use the word Adventures in the title advisedly. With the names Bill and Ted, I couldn’t resist the title, and for the two young men concerned it most certainly was an adventure, in the truest sense of the word; but not necessarily one they, or any of us, would care to repeat. However, it made them the men they were; and we are our father’s sons, are we not?

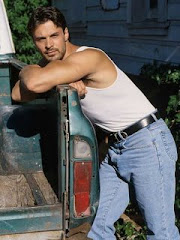

So let’s make the introductions. This is Bill Manley, circa 1941; Russ recalls he always had a sense of style in his clothing. He certainly looks very dapper here.

Bill was born in Florida in 1913 and enlisted in 1942, aged 29. He was trained, we think, as a radio/electrical mechanic; specializing in radar, then the latest technology. He rose to the rank of Corporal, but it was a bumpy path and he was certainly ‘busted’ at least once!

Ted Turner was born in Kent in 1919, one of two identical twins. This photo shows him in the RAF Volunteer Reserve Band in 1938, aged 19. He was called up for national service in November of the following year. He trained as an engine fitter and reached the rank of sergeant.

It strikes me that they both look so happy in these images; it was the calm before the storm. There’ll be some other characters appearing as well, connected in one way or another with Bill and Ted’s’ adventures.

Ted joins the RAF

Ted entered National Service, along with his identical twin brother Fred, on 1st November 1939. They completed initial RAF training at RAF Cardington, once the home of the famous R100 and R101 airships. Here is their course photo, some three weeks into the course. Pa is top far right; Fred is bottom far right, with his hands on his knees. This was the only time Ted and Fred served together; Ted’s career centred mainly on fighters, whilst Fred’s was with bombers. Their course NCO, the corporal in the centre, with his arms folded, looks a most useful chap!

I remember Pa telling me about the two massive hangars that were built to house the airships, each 812’ long and 157’ high. For a young man used to a family of 8 living in a 2-bedroomed cottage, the vast emptiness of the hangars must have been awe-inspiring.

Ted begins Trade Training

After this basic training – square-bashing, as it was known – where he learnt the rudiments of service life, marching, saluting, etc, Ted moved to RAF Henlow, near London, in early 1940. His notebooks are marked ‘Hut 89, No. 1(T) Wing, No. 1 Squadron. This is where he was taught about basic mechanics as they related to aircraft, but by April he had moved to the Fitters School, and was specialising in aero engines. His notebooks detail the in and outs of fuel pumps, starter motors, propeller shafts and lubricating systems. It must have been very intensive, with practical work mixing with classroom studies. Fortunately for Ted, and the RAF, this was the so-called phoney war period, before the Luftwaffe turned its sights on Britain.

Looking through my father’s notebooks of the time, it was intriguing to see how quickly his handwriting changed. At first, during his initial training it looks much as mine does now: untidy and uneven, nervous. But after a couple of months it settles down into the small, neat, confident style I remember him having from my childhood. Precise, and economical, the curves and loops are now tightened and drawn in. The style tells me he was maturing rapidly in these early war days. He was left-handed, by the way.

Ted in the Battle of Britain

When the battle of Britain started, the RAF became the Luftwaffe’s prime target. Ted was posted to RAF Duxford, near Cambridge, one of the major fighter bases protecting London. Most of the RAF’s fighter bases along England’s east and south coasts came under attack during the battle; high-level bombing, low-level strafing, and dive bombing interspersed with hit-and-run attacks by lone fighters. In this picture a bomb explodes on the parade ground at RAF Helmswell, no square-bashing for them.

It was during one low-level attack that Ted first saw action. He told me of being caught out in the open on the airfield, with no immediate shelter. Most servicing on fighter aircraft was done outside and not in hangars. He and his fellow airmen picked up their rifles and fired at the enemy aircraft, probably a Dornier or Junkers light bomber. The small calibre Lee-Enfield rifles had precious little chance of downing the bomber, and being out in the open was a perilous situation; but at the time he felt he was “doing his bit” when he told me the tale years later. Here a Spitfire sits under attack in its dispersal area, surrounded by clouds of dust raised by machine gun fire.

At Duxford Ted was part of 19 Squadron, the first to be equipped with the legendary Spitfire. In those days servicing was not centralised, and all the ground crew belonged to one particular squadron or other. This little video gives an idea of the ground crew’s various roles.

I’ve always loved this image of an airman re-arming a 19 Squadron Spitfire. It looks so much like my Pa, although it isn’t. It's actually a chap by the name of Fred Roberts. I wonder if he knew Pa?

Each aircraft had a dedicated team of an armourer, a fitter and the rigger, who maintained the airframe. There would be specialist technicians for the radio, instruments and electrics. But although he specialised in engines, like all ground crew, Ted would have been expected to help out wherever he was needed. One such duty was helping the pilots into their aircraft, the bulky parachutes and tight cockpits made getting into and out of the small fighters difficult at the best of times. And for some, more than others, for Duxford was also home to one Squadron Leader Douglas Bader, the famous legless fighter ace. My father recalled helping Bader into his aircraft on several occasions.

“He was not a particularly pleasant man to know and disliked by many of the men. He was short-tempered and looked down on anyone who wasn’t an officer.”

Pity then, the poor airmen who caught him in a bad mood! But his controversial ‘Big Wing’ tactics, massing the fighters against the incoming bombers, would prove very successful against the daylight raids on London and other major cities during the blitz. Such is the stuff of heroes.

When the Battle of Britain was over, the RAF took time to recover its losses and re-equip. Ted began to specialise on servicing and maintaining the famous Roll-Royce Merlin engine. Courses with Rolls-Royce at their factories in Derby and Glasgow were to keep him busy for almost two years, interspersed with duty at various operational airfields, during which time he also took up Freemasonry! He joined the Glasgow Lodge in January 1942, and remained a member throughout the rest of the war. At the time he also joined the Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes, another fraternal organisation! He must have missed his large family, and especially his twin brother. They were inseparable as children, especially in that form of mischief that only twins can manage. Grandpa couldn’t tell them apart, and so he would punish them both if one had been misbehaving! I think he must have found the constant round of courses, with no fixed abode, difficult without having some sort of social outlet. He was always a very sociable man, and would always greet everyone he met, whether he knew them or not, which mystified me greatly as a small child! So his Freemasonry and membership of the ‘Buffs’ was, I suppose, an antidote to the strictures of training and service life and to the loneliness at being away from family and friends.

Eager Eagle - Jimmy Nelson

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, some Americans couldn’t wait to join the war effort. The deeds of the Lafayette Escadrille, the squadron of American volunteers in the First World War, became legendary. When the Second World War came there was again no lack of volunteers, but the fall of France shattered the idea of a revival of the Lafayette. However, the RAF had inspired Americans with their gallant defence in the Battle of Britain. The New York Times wrote in August 1940, ‘During these crucial days the quality and spirit of the Royal Air Force have been written into the Great Legend.’ Many American pilots wished to be part of that legend and to fly that aircraft which had so captured their imagination – the Spitfire.

One such pilot was James (Jimmy) Nelson. Here pictured in the cockpit of his Spitfire and looking the epitome of a dashing young fighter pilot.

His tale is typical of many. Born in Denver, Colorado, in 1919, Jimmy learned to fly when studying at university. Having first enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force, he came to England in July 1941, and joined the new 133 Squadron, one of the three Eagle Squadrons in the RAF composed of United States nationals who wished to fight before their country had entered hostilities. The first Eagle Squadron formed in October 1940. In May 1942 the Squadron became part of Douglas Bader’s ‘Big Wing’, joining Pa’s 19 Squadron at Biggin Hill. When America officially entered the war, the Eagle Squadrons became part of the US 8th Air Force. However, Jimmy chose to stay with the RAF and served with distinction until the end of the war.

Bill joins up and starts training

Following America’s mobilization in December 1941, Bill was drafted in April the following year as a Private into what was then the Army Air Corps, soon to be known as the USAAF. His trade training took him all over the United States - Florida, Missouri, Illinois, and California. Russ also has some of Bill’s class notes placing him in Texas, at Shepard Air Base in Wichita Falls, where aviation mechanics were trained. This varied itinerary was due to the fact that at the time many technical courses were run by the manufacturers of the equipment rather than the fledgling USAAF itself, which had yet to develop its own training programme. It’s not clear what trade Bill took up, but our best guess, based on available evidence, is that he trained as a radio/electrical mechanic.

Russ remembers: “My grandmother said that the all men in daddy's family - she of course had known several generations of them - were always "strong minded" - by which homely phrase she meant, not stubborn, but smart. She often recalled when my daddy as a schoolboy had, on his own, worked though all the problems in a math book (this was when they were still living in the depths of the countryside) - and when checked by a teacher, it was discovered that he had gotten every one of the answers right, save one. So it might well be that during the war his aptitude for math would have gotten him shunted into work with those complicated systems.”

Bill arrives in England

In early 1943, having completed his training, Bill was posted to England, to RAF Rougham in East Anglia, home to several squadrons of B-17 Flying Fortress bombers, and part of the 94th Bombardment Group, 8th Air Force. A history of the 94th BG can be found here: http://www.8thafhs.org/ourhistory.htm Although the aircraft didn’t arrive until June that year, most of the ground mechanics arrived in March, having sailed from New York aboard a Liberty ship. This one is braving the Atlantic in winter, conditions on board must have been dire.

Having survived the crossing of the U-boat-infested Atlantic, I’m sure Bill’s first task was to secure his accommodation at the newly constructed airfield. Then began the intense preparation for the arrival of the aircraft and flight crews. Four squadrons, some 40 aircraft, were based at Rougham. Here one of the Fortresses checks for directions!

Russ’s Ma told him that Bill worked on “some new-fangled radar devices.” The use of airborne radar by the USAAF was very limited at that time, and only one bombing group were equipped with radar, the 482nd Pathfinder unit, based at RAF Alconbury, 52 miles away from Rougham. They were a very specialised unit, and led other non-radar equipped aircraft to their targets. So there was no airborne radar at Rougham. However, their remains another possibility. Towards the middle of the war, systems called Electronic Counter Measures (ECM) were developed. These were airborne devices designed to jam, or fool, enemy radars, be they on the ground, in aircraft or in the radar fuses fitted to some anti-aircraft shells. Whilst radars were secret, the principles were well known on either side. Countermeasures however, were even more highly classified because they negated the advantage of radar. To this day, electronic countermeasures remain the most hush-hush of devices.

Now from the time Bill was at Rougham, ECM was available to the Allies, though not in sufficient numbers for wide-scale use, so in a typical B-17 Squadron, one in five aircraft would be equipped. Rougham would therefore have had some eight specialised ECM fitted aircraft. This is what we think Bill may have worked on, not a radar device, but an anti-radar device. It would also explain to some extent why he never discussed the detail of his work, as it was extremely secret.

As in the RAF, Army Air Force mechanics, having been taught general servicing techniques would have then specialised, e.g. engines, airframes, armament, or radio and navigation. The guys who specialised in the radio and navigation equipment would have been the logical choice for the new areas of radar and ECM when they arrived later in the war, so it’s likely Bill would have followed that career progression.

Most radio and electronic servicing was carried out in buildings adjacent to, or in, the aircraft hangars. Rougham had a small building called the Radar Building, near the Control Tower, which housed the airfield radar and radio equipment. It is probable this is where the ECM equipment would also have been serviced and repaired, as the necessary facilities would already be in place. The building was more easily guarded than the hangars, and would have had much more secure conditions of entry and exit for such highly classified equipment. The Radar Building at Rougham still exists and was renovated in 2005. This could be where Bill actually worked!

The squadrons at Rougham took part in some notable raids, and like most Bomber Groups suffered very heavy casualties. The ground crew took great pride in their’ bird’, and its crew, and would await their safe return anxiously. Here ground crew work on a B-17 named Hell’s Angels.

But it wasn’t all work and no play for Bill. He managed to find time for a little romance too! Russ recalls some of his father’s possessions:

“And in another box I have some tiny wartime snapshots, some of them unknown buddies of his no doubt, and quite a few of Jackie, the English girl from the neighbourhood of Bury, whom he apparently loved very much - she was quite young, still a teenager but wanted to be a dancer - in some pictures she's doing the glamour girl pin-up poses in those modest two-piece bathing suits of the era - but sexy stuff back then I'm sure. And a couple of letters from her to him - poignant to read. In one of them, she says she misses him very much, and has saved the peel from the orange he gave her, and is keeping it on her windowsill. I know with the strict rationing in England at that time, an orange must have seemed like a grand treat indeed.”

It’s easy to understand the culture shock the young American airmen must have experienced on their arrival. This flat, foggy landscape and its inhabitants with their strange dialect. Just as well they brought a little bit of home with them; their language, customs, music and food soon filled airfields throughout eastern England. And how did the locals feel? Land, until then ploughed by shire horses, was now suddenly under concrete and under guard. Jazz, blues, jive music, chewing gum. And one can only guess at what they made of the Wabash Cannon Ball, one of Bill’s favourite tunes.

Did Bill and sweetheart Jackie dance to it at the Junior NCOs Club or the village Church Hall? I do hope so! However, by the look of things, the boys couldn’t wait for Jackie to arrive!

And I’m sure Bill and his comrades played it on a wind-up record player as they sat around the stove pipe heater in their hut, thousands of miles from home in this cold and clammy foreign land; hoping their crews and aircraft would return safely to Rougham. Sadly, in those early days, many did not.

Ted at RAF Turnhouse – the mid 1940’s

In February 1943 Ted was promoted to the rank of Sergeant and posted to RAF Turnhouse, near Edinburgh. This was where the battle-weary fighter squadrons were rested and re-equipped, away from the front line. Here is the photo he sent to his childhood sweetheart back home in Kent, on the back, in that neat hand, a simple message ‘With love from Ted’.

It shows a young man who has matured during four years of war, he looks, more confident, more self-assured.

He maintained his membership of the Masons, as the receipt for his membership of the Bo’ness Lodge shows. But before the year ended he was back with Rolls-Royce at Derby for yet more training, but this time it was to have an American twist.

Next time . . .

By the end of ‘43, plans were well advanced for the Allied invasion of Europe and also for a renewed offensive in the far-east. 1944 was to have big things in store for both Bill and Ted. Travel and action, hardship and a VIP-lifestyle, all will figure in Part 2.

.JPG)

2 comments:

What a wonderful post! I've only begun to delve into it. Thank you!

Thank you kindly Sir! We aim to please.

Post a Comment